What do you read when you do a residency? This is a surprisingly central question when you are isolated from your family and friends, focussing on your work and living in your own head, as you often end up when on residency (the only actual humans I spoke to over the weekend were shop assistants and baristas). What you read can colour the residency and your research, and the decision about whether to let this happen or not can be a tough call.

Elizabeth Gilbert has recently released a book about a Victorian era, female botanist and my friend Kate had suggested perhaps I should read that while on residency. Despite other of her books being made into Julia Roberts films, apparently the lady can write. But as I stood with the book in my hand (at the airport, not very organised), I remembered how reading 'A Passage to India' while in Rajasthan really hurt my brain and sent me on a massive post-colonial guilt trip, which in retrospect I don't think was helpful. I put the volume back on the shelf and picked up my borrowed copy of volume 1 of Simon Schama's 'History of Britain'.

|

| December Saints IV, 2005 |

It's no secret that I love British medieval history (see above) and Schama's wonderfully engaging book also introduced me to the even more fascinating stone age world of prehistoric Britain, in particular the ancient settlement of Skara Brae in Orkney. And then, last night when I was forced to watch free-to-air television (having finished History of Britain, and watched all my Game of Thrones, Pride and Prejudice and 30 Rock), a documentary about the sacred places of Britain came onto SBS.

|

| Skara Brae, image courtesy of orkney.com |

Basically Britain is littered with remnants of ancient (read: thousands of years old) villages, structures devotional sites, including one field which was a collection of filled-in 12 metre deep flint mining pits (bizarre because there was plenty of flint at the surface and no need to go digging for it). Some places are perhaps a mound in the countryside somewhere, which will be dug to up to reveal a tomb. Skara Brae, a Neolithic village abandoned as the climate worsened in Scotland about 2500BCE, was concealed beneath sand for millenia, until a massive storm uncovered it in 1851. Revealed in the ruins of this village were layers of occupation, a forgotten society, inhabitants who had begun to shape and impose their beliefs on the land.

|

| Long Man of Wilmington, image courtesy of Wikipedia |

Humans mark the landscape. Sometimes it's really obvious through environmental degradation, building pyramids, damming a river. Sometimes its more subtle.

|

| Despite a wide perception that moors are wild, naturally pristine places, many moors in Great Britain, such as those in the Penines, were the result of widespread tree-felling that occured in the Mesolithic era. Thanks to Wikipedia for the image, BBC World service for the story I heard yesterday about the ecology of moors! |

Look at Ash Island. The cattle grazing, industrial sites and wholesale land clearing have left the most obvious marks on the land, and the environment is the poorer for it. There is little evidence beyond 2 palm trees (one of which is now dead) and the remnants of an old jetty to mark the Scott sisters' 20 years of occupation of Ash Island. The majority of the island's pre-existing plants and trees were left untouched by the Scott family. Historians have noted the few discoveries of occupation of Aboriginal occupation, although an area has been designated where remains of middens and other evidence are probably buried.

|

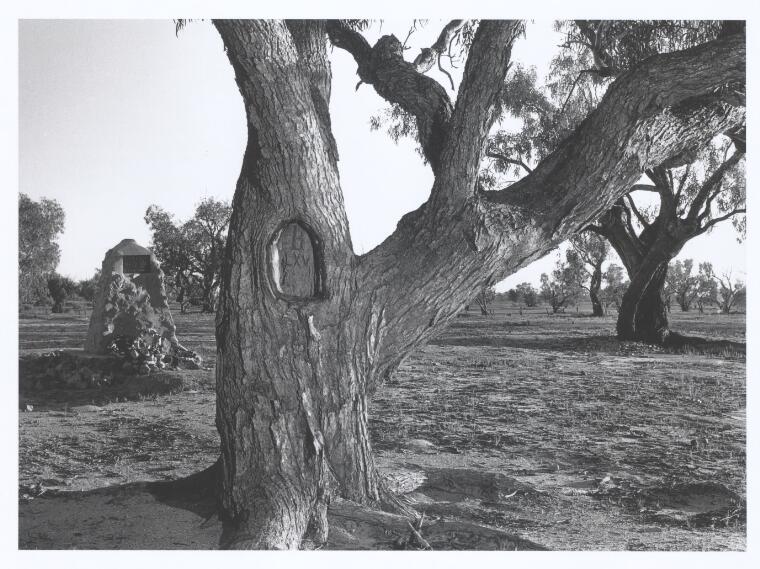

| Burke and Wills 'Dig Tree', image courtesy of National Library of Australia |

Yet these more subtle occupations have shaped the occupants and the land. The 20 years of sheltered life that the Scott sisters enjoyed, on an island that supports a huge variety of butterflies and other living things, allowed them to expand their knowledge and skills into professional careers, which sustained them long after their departure from the island. Ok, sure, gender politics held them back from having the careers that their talents truly deserved, but by the standards of the day, their career fulfilment would have been unknown to most women. They left their permanent mark in the form of their considerable body of work, some of which is still used by scientists today, even in the days of photography! And while their work can be seen as part of a wider process of colonisation through the classification of the environment, their legacy included a catalogue of local flora and fauna which is now used by the Kooragang Landcare group to restore the environment at Ash Island.

|

| The Lone Palm, Ash Island |

Ash Island's abundance of plants and wildlife sustained and nourished the Awakabal and Worrimi people for the many thousands of years of their occupation of the area. While early European settlers liked to think that the Indigenous inhabitants had done almost nothing to shape the land, we know this is not true. In particular, in such a fertile area, there would have been deliberate harvesting and cultivation of particular plant species for, among other things, food, medicine and weaving. It might have seemed like Captain Cook had stumbled on an untouched wilderness, but if you were to look with different eyes you would know the truth.

|

| Detail from my Scott Sisters sample piece |

I've been thinking about this for a week now, but watching the BBC documentary last night gelled it for me. We mark the land, the land marks us. We are inextricably linked. There are layers of occupation, of interaction, that are left on the land, if you know how and where to look. The land tells stories. It conceals and reveals them. It reminds us of who we were, what we did, and what the land did to us.

So there you go, I took a book which I thought would be completely unrelated to the Scott sisters (I also thought about them while watching 30 Rock and Pride and Prejudice, which are after all created by women who have struggled with the realities of career and gender) and turned it into the central thesis of my residency. I wonder what would have happened if I'd picked, say, the History of Concrete???